Palazzo Massimo alle Terme

If you are planning a visit to the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Museo Nazionale Romano, here is everything you need to know.

Plan your visit

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, hosts one of the largest collections of ancient art in the world. The Museum is part of the museum group Museo Nazionale Romano or National Roman Museum, founded in 1889.

You can buy a combined ticket and get access to all the museums which include: the baths of Diocletian, Palazzo Massimo, Palazzo Altemps and Crypta Balbi.

Palazzo Massimo should be on your list of museums to visit when you go to Rome. It feels clean and modern, with beautiful displays and have good descriptions. Every floor has WC and is connected with a lift. There are not as much people here as there are in other tourist places in Rome, and you can stroll around not much disturbed by other people.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, constructed between 1883 and 1887, is an imposing building in the style of the late 16th century by architect Camillo Pistrucci. Initially, it served as a Jesuit college until 1960. In 1981, the Italian state acquired it to extend the Museo Nazionale Romano. After careful restoration by architect Constantine Dardi, the building opened to the public in 1995, with subsequent floors completed in 1998.

Today, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme houses one of the largest collection of Ancient Art over four floors.

The Ground Floor

Greek originals and Roman portraiture

The ground floor of the museum houses a remarkable collection of artworks dating from the late Republican era through the early Principate, up to the Julio-Claudian period.

One standout piece is a colossal seated goddess statue, skillfully crafted from multicolored marble using a polychrome technique. While currently restored as Minerva, it likely originally represented Magna Mater-Cybele, a Phrygian goddess. The statue’s exquisite details and use of gilded alabaster in the clothing suggest it was used for worship, and its drapery technique echoes classical sculpture.

The First Floor

Sculptures: The Hall of Masterpieces

As you ascend the grand staircase to the first floor, you’ll encounter a series of statues. Once again, the majority of these sculptures are replicas and adaptations of Greek originals, portraying deities like Zeus, Apollo, and Dionysus. These pieces originate from the villas of Latium.

The first floor revisits two key themes previously explored on the ground floor. One theme delves into the representation of imperial figures, spanning from the Flavian period to late antiquity. The other theme explores the creation of “fantasy” sculptures, crafted to adorn the villas and residences of the ruling elite.

The Second Floor

Frescos, Stuccoes and Mosaics

The second floor is a treasure trove of high-quality paintings and mosaics from opulent residential complexes. These artifacts offer profound insights into the opulence and intricate decorative designs that adorned the homes of the Roman aristocracy. They also serve as valuable documentation of the exceptional painting craftsmanship in Rome and Latium, complementing what we’ve learned from the Vesuvian cities.

While the number of preserved cycles in Rome may be limited, their refinement is unparalleled. To preserve their authenticity, the museum has made every effort to present them in a way that respects their original locations. This approach allows visitors to appreciate the connection between these exquisite frescoes and the architectural structures they once graced. This connection is fundamental to understanding Roman painting, which was primarily a medium for mural decoration.

Statue of Augustus from the Via Labicana

The statue of Augustus from the Via Labicana is a grand depiction, showcasing his regal attire, and a studied pose. The statue is rich in symbolism, with the toga symbolizing Roman tradition and his veiled head signifying his role in sacred rituals.

The missing right arm and left hand leave room for speculation about his exact actions. He might have held a patera for sacrifices, but other possibilities like the lituus can’t be ruled out. There’s also the likelihood of a volumen or scroll, hinted at by the nearby cylindrical scroll case (capsa).

This portrait follows the Prima Porta style, likely created in 27 BC when Octavian became Augustus. The attention to detail captures the emperor’s aging features, including wrinkles and facial folds.

While some believe the statue was crafted after his appointment as a pontifex maximus in 12 BC, the veiled head doesn’t necessarily imply this position. Various clues suggest that it likely dates to the late 1st century BC, not the end of Augustus’s reign.

Interestingly, the statue employs Hellenistic sculptural techniques, using different marbles for distinct parts, emphasizing its artistry and historical significance.

The Niobid of the Horti Sallustiani

In 1906, a remarkable Greek sculpture was discovered in Rome, hidden underground near Piazza Sallustiana, possibly to protect it from 5th-century barbarian invasions.

This sculpture portrays a young girl fallen on a rocky surface, desperately trying to remove an arrow lodged between her shoulder blades. This arrow, likely shot by Apollo or Artemis under the orders of their mother, Leto, was retribution for Niobe’s boast that she was more fertile than the goddess. The tragic tale is recounted by Homer, dramatized by Sophocles, and illustrated in various ancient artworks.

Exquisitely carved from Parian marble, the sculpture is a fragment of a larger pediment decoration. Its origin has been debated, possibly from a workshop in Magna Graecia or the Peloponnese, combining Doric and Ionic elements, or an Attic creation reminiscent of Alcamenes’ work. According to Eugenio La Rocca, the sculpture is associated with two other figures in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, dating them to around 440 to 430 BC, despite excavation uncertainties that fueled the antique market.

These sculptures exhibit striking similarities in their head structure, facial expressions denoting amazement, realistic hair, meticulously crafted drapery, and the incorporation of metal attributes. The exposed flesh is rendered with precision and vitality, accentuating the adolescent’s charms.

The Niobid cycle may have been adapted for a Roman place of worship, possibly the temple of Fortuna Publica on the Quirinal, creating an ideological tribute to the future emperor, much like Gaius Sosius did in Circus Flaminius after victory in Egypt. This sculpture exemplifies the enduring link between art and politics in ancient Rome.

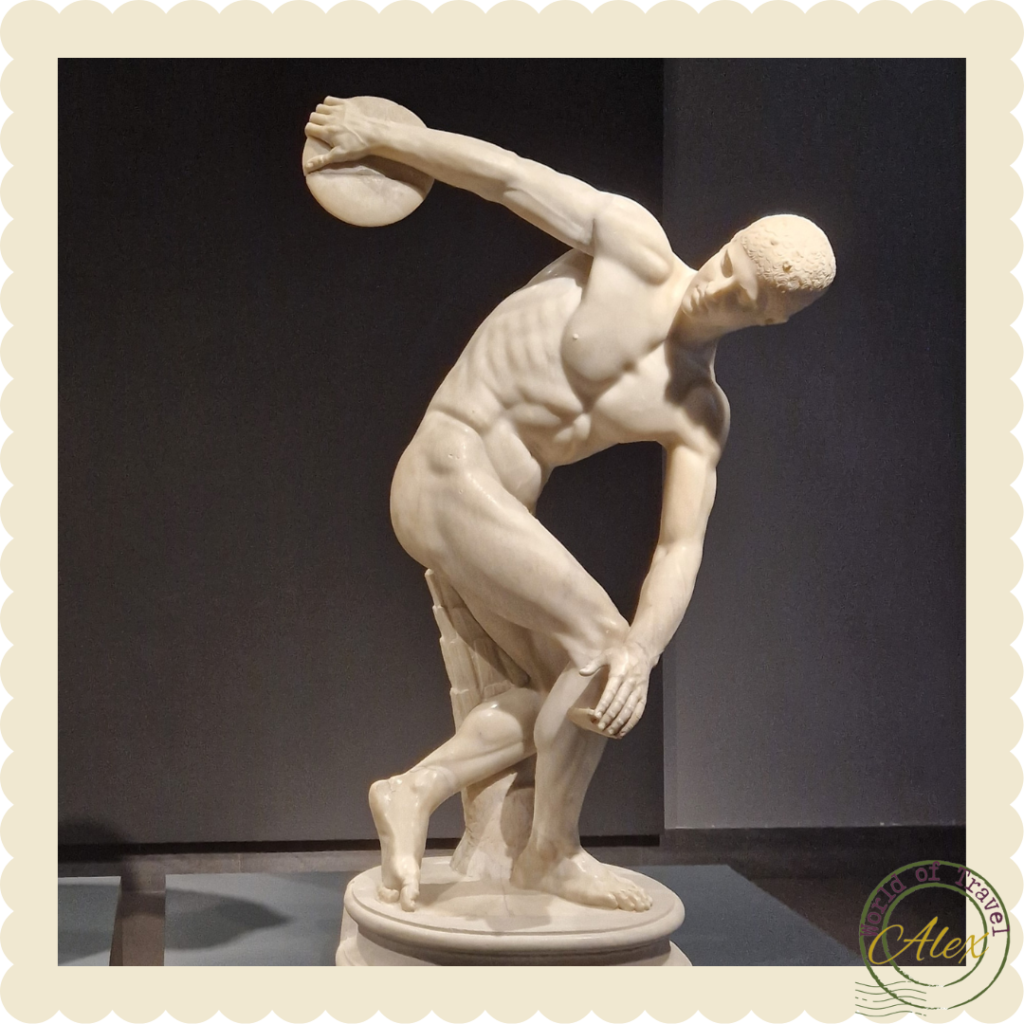

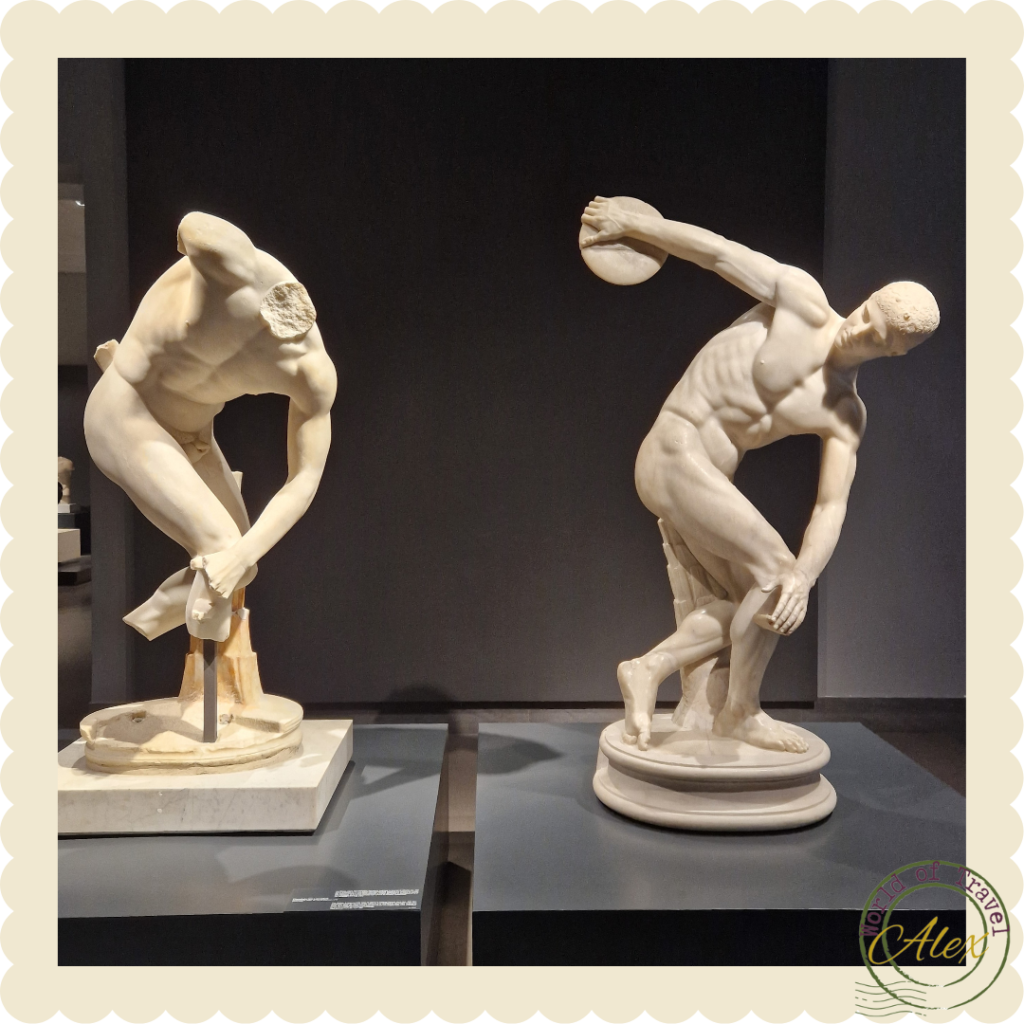

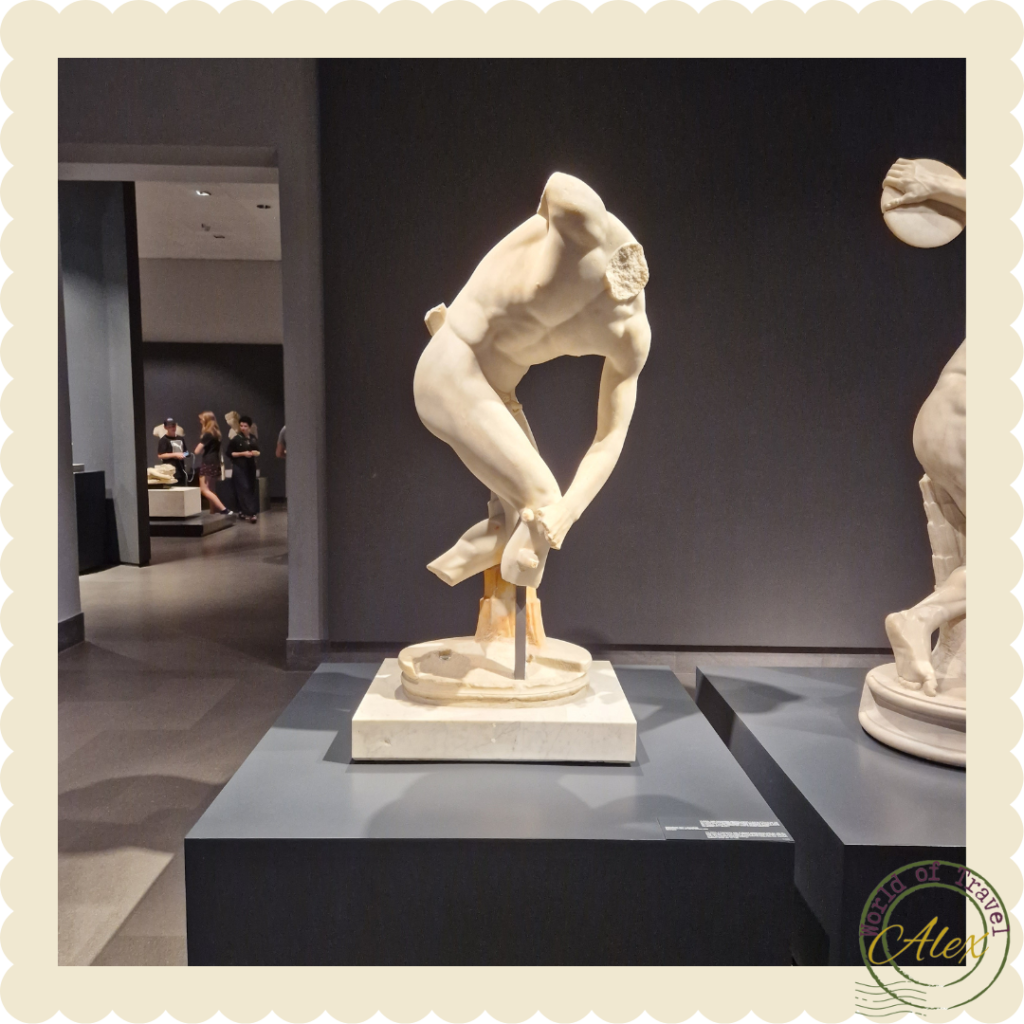

The Lancellotti Discobolos

Named after the Lancellotti family who once owned it, this statue was discovered on the Esquiline, part of the Horti Lamiani, which came under imperial possession during the early Julio-Claudian period. Dating from the Antonine period, 96 to 192 AD, this sculpture masterfully depicts an athlete in the act of throwing a discus and is considered one of the finest replicas of Myron’s Discobolos.

Myron originally cast the Discobolos in the 5th century BC. He aimed to capture a dynamic moment in the act of throwing, with meticulous attention to geometric precision.

The athlete, naked and poised to throw, stands with the discus held in his right hand, muscles taut and body bent forward. The intricate details, including facial features, veins, and musculature, align with the Severe style of sculpture.

The statue’s two-dimensionality suggests it’s meant to be viewed from a single angle, emphasizing the concentrated power of the athlete. The precise identity of the athlete portrayed remains a mystery, but the Discobolos remains a celebrated symbol of Greek athletic prowess and discipline.

The Villa di Livia

The fresco from the Villa di Livia offers a captivating glimpse into a world of lush garden paintings. Livia, the wife of Emperor Augustus, had her winter villa on the Via Flaminia just north of Rome at Prima Porta. The grand 5.90 by 11.70-meter room that housed these remarkable frescoes was expertly detached for conservation in the 1950s and has since been meticulously restored and reassembled.

This room is a masterpiece, where an open garden comes to life on every wall. The garden is a rich tapestry of laurel trees, palm trees, pomegranate-bearing branches, vines, rare plants, and a profusion of vibrant flowers. Birds gracefully soar against a brilliant blue sky, creating a seamless, enchanting scene that flows throughout the room. There are no architectural divisions, just a dual enclosure—a middle-ground cane and wicker fence leading to a verdant passage and a marble balustrade enclosing niche trees like pine, fir, and plane trees.

This love for nature extended to Vesuvian domus, where peristyles replaced atriums, transforming into lush gardens with trenches and grotto-nymphaea, celebrating diverse seasonal plants.

The illusionistic painting genre was immensely popular, invoking the senses with its vivid colors, fragrances, and the sounds of swallows in flight and fountains babbling.

Accessibility and facilities

The museum are fully accessible to individuals with limited mobility, featuring designated pathways that bypass any structural obstacles. The entrance, located to the right of the stairs, provides an intercom for any needed assistance. Additionally, there are elevators and accessible restrooms available on both the ground floor and the second floor.

Public transport

Metro: A and B lines to “Termini”

Opening times and admission

Tuesday to Sunday: 9:30 am to 7 pm

(last admission 6 pm)

The first Sunday of each month, the entrance is free.

Combined ticket to all four National Roman Museum sites

This allows one entrance to the Baths of Diocletian, Palazzo Massimo and Palazzo Altemps, within a week of purchase. Please note that Crypta Balbi is temporarily closed.

Full price €12

Reduced €8

Available for EU citizens aged between 18 and 25, upon presentation of a valid identity card.

Tickets for Palazzo Massimo alle Terme:

Full price €8

Reduced €2

Available for EU citizens aged between 18 and 25, upon presentation of a valid identity card.

A pre-sale fee of € 2 applies to all tickets purchased online

Since the 15th of June and until the 15th of December, 2023 all tickets will be charged 1 additional euro in solidarity with Emilia Romagna.

The MNR adheres to the Roma Pass Card.